Bill Akin is a longtime Montauk resident who has a special connection with the Carl Fisher House: his parents bought it from Fisher’s widow in 1956. His observations about the property over 65 years are charming, poignant and powerful.

For the last few years I have been nurturing a relationship with a red oak tree in my front yard. I call him Ralph, choosing a man’s name, as at seventy-five, my circle of male friends is dwindling.

While this behavior might seem strange, I have known Ralph longer than anyone I can think of with the possible exception of an old friend suffering from cirrhosis fifteen hundred miles away in south Florida.

Most days I walk by Ralph as I head down my driveway to pick up the morning paper. This affords me, or us, a few quiet moments to appreciate the world apart from the homo-centric universe that will likely dominate my day. No doubt it will be another day when, aside from political nonsense, news concerning human destruction and the exploitation of everything – plants, animals, the atmosphere, and the oceans – simply anything that does not walk on two legs, will flood the news while simultaneously being ignored by most people: deforestation, species extinction, ground water depletion, over fishing, ocean acidification, a rising sea level, dead zones, etcetera.

But this is my time on earth, and I am grateful to have Ralph.

My wife and I built the house we now occupy at the tip of Long Island in Montauk, New York, twenty-eight years ago. Before we broke ground, our parcel had been part of a much larger, somewhat neglected 1920s estate. My father purchased the property in the ’50s when I was a young boy. Off to one side was a mostly overgrown dirt road originally intended as a service entrance. As a child I wandered down the trail In August to pick blackberries. The best berry picking was on the opposite side of the path from a single skinny tree. No more than twenty feet tops, it was still much taller than the few bayberry bushes scattered across acres of grassy fields.

For decades prior to construction, my wife and I lived in what had once been a caretaker’s cottage on the opposite side of the estate. I would occasionally walk down the old path, but the patches of blackberries had gradually become overgrown as other dominant flora flourished. Many years later when our family subdivided the estate, I ended up with a few acres that included the old path and what had become a substantial oak.

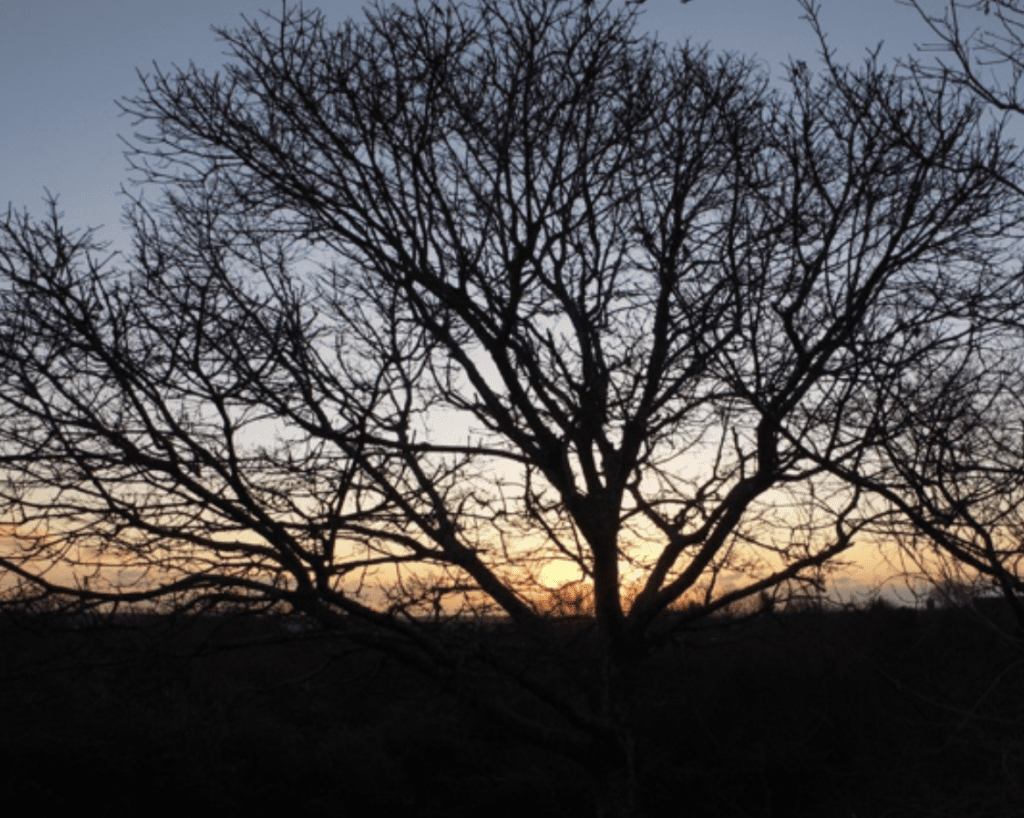

Not long after, my wife and I agreed on building plans that incorporated the old path as our driveway. We located the house up a slight rise with the oak bordering the right side. The result: what for half a century had been nothing more than a back of mind memory was now fifty feet tall, and greets us every time we look out an east-facing window or ride up the driveway. Christmas mornings its towering trunk and skeletal branches stretch across the dawn sky and the rising sun.

Nevertheless, how it is that at age seventy-five I have come to bond with this tree? After all, lots of people have a tree in their front yard. When I think about it, which isn’t often, I credit countless childhood hours alone in forests or fishing in local ponds. My parents were over forty when I was born. Mother was busy with social obligations, and Father was running the family business. My only sibling, a brother, was almost nine year older, which seemed like a century to me at age six. He was born in the 1930’s, I arrived the next decade. By the time we both reached an age considered maturity, the nine years had become two distinct generations. His being Ayn Rand, mine Alan Watts. He was into cars; I was comforted by wilderness.

Decades later, when we had grown much closer, he died at age sixty-six in a crash while testing a vintage endurance race car his company had restored. By then our parents had passed away, and while I am happily married — no children — and enjoy a warm relationship with my nieces and nephew, I have no immediate family.

One friendship has, however, endured: my bond with the land where I live.

If you ask someone about the plants, trees, and animal life around their home, I suspect most will envision a somewhat static setting. But when you inhabit the same land for what is now sixty-five years, as I have, the changes are remarkable. Not only are the trees many times taller, but fields of grasses have given way to a variety of dense shrubbery. My childhood panoramic view encompassing the ocean, Lake Montauk, and Long Island Sound is now obscured by trees, and has shrunk to a narrow glimpse of the south end of the lake. The dirt roads I hiked unsuccessfully hunting rabbits with bow and arrow, are now paved.

The animal life has also dramatically changed. Every year there are fewer song birds. Both pheasant and quail have disappeared (not enough grassland), replaced by tree-dwelling creatures such as possums, grey squirrels, and wild turkeys. On the ground, the population of white tail deer has exploded. Dog ticks hooked up with three or four different blood-sucking species and their associated diseases, while the numbers of summer tourists and second homeowners have outpaced even the deer.

By earth time, it wasn’t long ago when Montauk was Native American territory. If you know where to look, and I do, you can still find signs of their existence hidden in our wilderness. As my relationship with Ralph has developed, I have been thinking more about how Montauk’s original inhabitants might have lived. Did they also witness changes in only a few decades?

I doubt it, as Montauk’s recent terrestrial history is unique. Today the land is still adapting evolving from two centuries when the hills and hollows were was cattle country. Herds were driven out each spring from up island, feeding along the way on any number of grasses, shrubbery and who knows what. Montauk’s windswept landscape became the depository, seeds and all, at the end of the digestive process. As a result, our local flora is more diverse than any other on Long Island, and surely unlike what Montauk’s native inhabitants encountered.

But before the white man, before the sailing ships, before horses and cattle, even before wheels, there was wilderness. Perhaps a few seasonal camps, burial grounds,and small cultivated areas for squash and corn. It is unlikely that the forests and lakes changed much from one generation to the next.

Conjuring up a picture of this time, it’s not hard to imagine how these original locals, along with other North American peoples, developed deep bonds with their environment. The wind, the rain, oceans and lakes, animals, fish, even trees.

This reverence is palpable in countless Native American prayers and poems. For example, from Central California, this Yoguts prayer:

My words are tied in one with the great mountains,

with the great rocks,

with the great trees,

in one with my body and heart.

All of you see me, one with this world.

Or this Navajo chant:

The mountains, I become a part of it…

The herbs, the fir tree, I become a part of it,

The morning mists, the clouds, the gathering waters,

I become a part of it.

The wilderness, the dew drops, the pollen…

I become a part of it.

Reading these prayers I am overwhelmed by the compassion, respect, and love they reveal for the earth. I can’t help wondering how this connection was lost? How did we, “the civilized societies,” the “smart people,” evolve a consciousness that departs so dangerously from this awareness? This respect? This compassion? This love? Accelerating towards… what? All while we do our best to deny it. How could we get so much right, and still get so much wrong?

Walking up my driveway one morning last week I wondered if I had gone bonkers: an elderly man with a respectable education who talks to trees; someone who has benefited greatly from modern-day life, but who believes an ecological catastrophe is likely unavoidable.

There, under his arboreal arms, I asked Ralph, “What can we do?” In a flash, centuries of answers erupted up through his roots, radiated from his bark and rained down from his branches: “Pay Attention! Do Not Squander This Earth!”

Treat the earth well.

It was not given to you by your parents,

It was loaned to you by your children.

We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors,

We borrow it from our children.

— Ute prayer