By Henry Osmers

Similar to just about any other community on Long Island, Montauk has a number of old and historic buildings. For example, the Montauk Point Lighthouse, Second House, Third House, Montauk Manor, and the Carl Fisher Tower are visible reminders of bygone times.

Also like other communities, some old and historic structures have been lost. This article takes a look at a number of these places, all of which had their place in Montauk’s unique history.

First House

The First House was the first of three dwellings built at Montauk. All three had a role to play in the organization and maintenance of the cattle and sheep that spent each season grazing on the fields of Montauk.

First House was built in 1744 and rebuilt in 1798. The keeper who lived there had the responsibility to enter the earmarks of the animals on the Common Pasture list and to make certain that fences were in good repair. He kept a watchful eye on the sheep grazing between First House and Second House, located about four miles east.

The house also served as a hostelry, and must have been a welcome sight to weary travelers bound for Montauk during the 19th century; especially after crossing the sandy, barren stretch known as Napeague, where mosquitoes feasted on summer travelers in great numbers. But upon reaching the hills of Montauk, the breezes intensified and insects disappeared.

As wonderful and serene as that sounds, the visitor noted that there was a dark side to living at First House; as “many a time have the family been roused on a stormy night to receive the survivors of a castaway crew. Often, too, a sadder duty falls upon them; that of burying the unclaimed bodies that are washed ashore. I do not envy them their lonely post.”1

One of its last occupants, Ulysses L. Payne, moved to Second House in 1900, and for the next decade the history of the house became quiet, with individuals occupying the house for brief periods.

It is generally accepted that First House was destroyed by fire in 1909, but no Long Island newspaper carried the story. According to former East Hampton Town historian Jeannette Edwards Rattray (1893-1974) in 1968, she was told by Benjamin Wells (1882-1978) of Sag Harbor that First House was destroyed by fire at that time. Said Rattray, “I had been trying for 30 years to find out when that [house] was destroyed.”

William Bassett, who lived at First House from 1903-1906, said, “It was a nice house, a story and a half, with three bedrooms upstairs and one down. Much like Second House before that was built onto.” When asked why he left in 1906, he replied, “The sheep drove me off. I got tired of fencing. One foggy day I went fishing. I had an eight-acre field of corn, up two and a half feet. When I got home, the sheep had got through the fence and eaten it down to the ground.”2

Today, nearby First House Cemetery is easily accessible, but to reach and find the site of First House requires a hike through some wooded terrain. For the sake of Montauk history, it would seem prudent to create a path to the site and signage indicating First House’s place in Montauk’s frontier days, as well as being a place of safety and repose after enduring such a difficult trip from “up-island” long ago.

Lathrop Brown Estate

Lathrop Brown (1883-1959) was active in government and real estate, and had homes on Long Island, New York City, Boston and California.

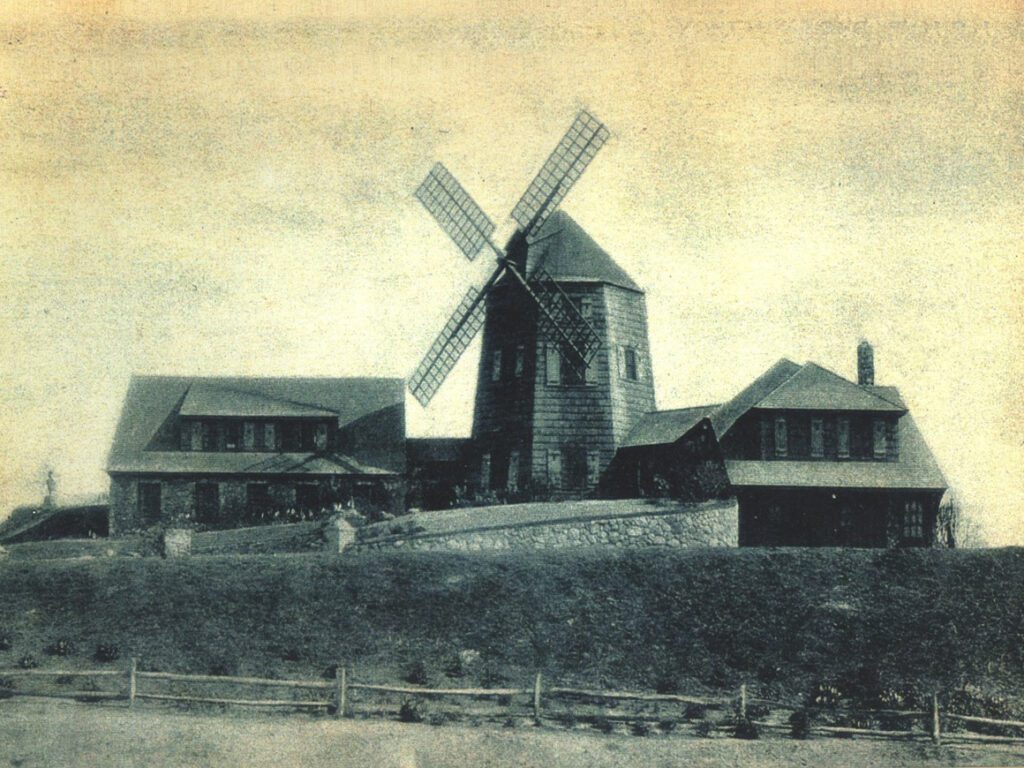

In the spring of 1922 Brown purchased a windmill in Wainscott and moved it to property at Montauk which he purchased from the Benson Estate. The mill was built in Southampton in 1812, moved to Wainscott in 1869, and stood on the property of Nathan C. Howell.

Brown’s 30-acre property, which included 1,000 feet of waterfront, and situated on the cliffs close to the Wyandannee Inn and along the “Old Point Road” (later Old Montauk Highway), was a place of scenic beauty, enhanced by the nearby Montauk Point Lighthouse. Brown added a cottage adjoining the mill, which was known as Windmill House.

Lathrop Brown and his wife showed their generosity to soldiers who served in World War I by annually having about a dozen of them spend a couple of weeks at the Windmill House. Fishing trips were a part of the activities the men enjoyed.

Modern times reached Windmill House in 1936 when electricity was installed. By 1938 the power lines reached the Montauk Lighthouse, with the light itself electrified on July 1, 1940.

Although the great hurricane of September 21, 1938 caused devastation across eastern Long Island, Lathrop Brown was one of the few in Montauk to take Weather Bureau warnings seriously, and had the house secured, including lashing up the windmill arms. Fortunately, little damage was said to have been caused there by the storm.

With the United States involvement in World War II, Montauk’s military role took center stage. Plans to development an Army installation on the property containing the Brown Estate were being prepared, and Brown was given six months to remove any buildings from the property.

On July 1, 1942 the windmill was returned to the village of Wainscott and placed on the property of the Georgica Association by new owner Professor George W. Pierson of Yale University.

Meanwhile the Brown Estate became part of Camp Hero, an Army base that remained active through and after the war. The cottage was relocated to a site on the Old Montauk Highway near Gurney’s Inn by rancher and polo player D. Stewart Inglehart (1910-1993) in 1942 and purchased by editor, journalist, and writer, Margaret Cousins (1905-1996) in 1955. The garage was moved to the old fishing village in Montauk by Mary Smith. The windmill still stands on the spot it was placed in 1942. Condition of the other structures unknown.

Montauk Island Club/Deep Sea Club

One of developer Carl Fisher’s Montauk projects, it opened in June 1928 on Star Island, offering dinner and dancing, and attracting an A-list crowd. However, it was also reported as being “the most exclusive gambling resort in the East.” During its “heyday,” considered to be 1928-1936, featured a speakeasy during the Prohibition Era, and, according to local lore, a notorious brothel.

The Club lost no time developing a checkered history surrounding suspicions of gambling practices, resulting in a number of police raids over the years. A raid on September 21, 1929 resulted in the confiscation of about $30,000 in gambling paraphernalia. During a raid in August of 1930 it was said that New York City Major Jimmy Walker was in attendance but escaped out a window!

Despite this notoriety the Montauk Island Club rolled on. It eventually closed in 1950, but reopened in 1955. But it didn’t take long for the law to descend upon the Club. A month later a raid resulted in the confiscation of a wire-tapping system and a dice game. The Club suddenly closed soon after, and, not surprisingly, its employees left town!

New management took over, opening the business as the Deep Sea Club on July 11, 1959. However, the new club would also have a turbulent history, beginning with the theft of $1,500 from a strongbox by an employee of the club about a year later.

The Club went through a number of name changes, including the Deep Sea Club Restaurant (1962), and the Deep Sea Marina & Restaurant (1963).

In the mid-1970s the property was known as the Deep Sea Yacht & Racquet Club. A fire in the kitchen area of the club in 1982 was termed “suspicious,” followed by thefts from yachts and boats in 1983. There was discussion about the creation of condominiums and the preservation of the site in 1987.

Any future plans for the Club were destroyed when, on June 1, 1989, a fire swept through the historic building. Firefighters from Montauk, East Hampton. Amagansett, Springs and Sag Harbor fought the blaze, which spread to all three levels of the building. Arson was deemed to be the cause.

Plans were later announced that the gutted-out building would be razed and that there were plans for condominiums and a restaurant on the site. Any plans submitted were rejected by the Planning Board and articles about development ceased in 1990.

Montauk Surf Club

Originally referred to as the “bathing casino,” in 1930 Carl Fisher brought it into his comprehensive Montauk development as the “Montauk Surf Club,” which would include “large Tom Thumb golf course, the improved grounds and walks, and the enclosed grill.”3 It achieved success, but with the collapse of the Carl Fisher’s fortunes in Montauk by 1932, the Club was sold to the Montauk Beach Development Corporation, which planned to operate the club in conjunction with its Montauk Manor Hotel.

Over the succeeding years, the Surf Club enjoyed significant success, featuring its huge salt water pool, annual bathing beauty contests and water shows. It was taken over by the U. S. Navy in 1943 during World War II. It introduced night bathing in 1949.

The new Surf & Cabana Club was opened in 1955, and many aquatic events were held there over the next ten years.

By the late 1960s there were reports of real estate developments to take place in the vicinity of the Club. A fire on February 8, 1969 caused considerable damage, completely destroying the Club’s front portion which included offices and a dress shop. The Club’s general manager, Frank Tuma Jr., said the Club’s pool had not been used for three years. It seemed as though the days for the Montauk Surf Club were numbered.

A few months later, the Montauk Improvement Company announced plans to reconstruct the Surf Club, but these plans did not materialize. Finally, in a move that gave the Montauk Fire Department “some practice,” the Montauk Surf and Cabana Club was destroyed on July 21, 1969. Frank Tuma Jr. announced there were plans to build a new Surf Club on the site but these plans never came to fruition.

Today, the site is marked by a development named, appropriately enough, the Surf Club at Montauk, featuring duplex suites and contemporary design.

Sandpiper Hill

This magnificent estate was designed and built by Richard Webb for Walter and Alys Mary McCaffray in 1928. Situated near the cliffs below Miller Avenue in Ditch Plains, the 14-acre estate was considered one of Montauk’s showplaces, commanding a beautiful view of the Atlantic Ocean. Its center section sported a tall windmill, which, according to the Montauk Chamber of Commerce, was “attractive, but far from functional.” Mr. McCaffrey, who was a Wall Street broker, and his wife, were great supporters of the Church of the Little Flower (now St Therese of Lisieux Church) in Montauk, and contributed generously to its construction in 1930.

Walter McCaffrey died in New York in 1935. Mrs. McCaffrey continued to live at the estate for several months until closing it up and moving to France, where she lived until her death in 1940. She willed the estate to the Order of the Society of Jesus, based in the Bronx, New York, stating that the “house and property be used for the purpose of providing a home or retreat for ailing or retired Jesuits.”

In the 1940s the estate was sold to Sidney Rheinstein (1887-1968), a member of the New York Stock Exchange for over 50 years, who maintained the house until his death. In the early 1970s, due to the effects of erosion, a portion of the house was actually hanging over the edge of the cliff. In 1973, photographer Peter Beard, who lived a short distance away, acquired the center section of the house which included the 50-year-old windmill and had it moved to his property. The two remaining sides of the house were relocated to sites along the Old Montauk Highway west of the village.

The windmill was destroyed by fire in July, 1977. Lost were Beard’s extensive photos and papers of his trips to Africa, as well as a collection of old Montauk photos, and personal memorabilia. The greatest losses were paintings by Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol.

Today, the site of Sandpiper Hill sits bare, continually disintegrating from the ravages of erosion, leaving only a memory of a once beautiful dwelling that was much appreciated by the Rheinsteins. Adjacent to the site is the appropriately-named Rheinstein Park.

Andrew Thomas/Elbert McGran Jackson Estate

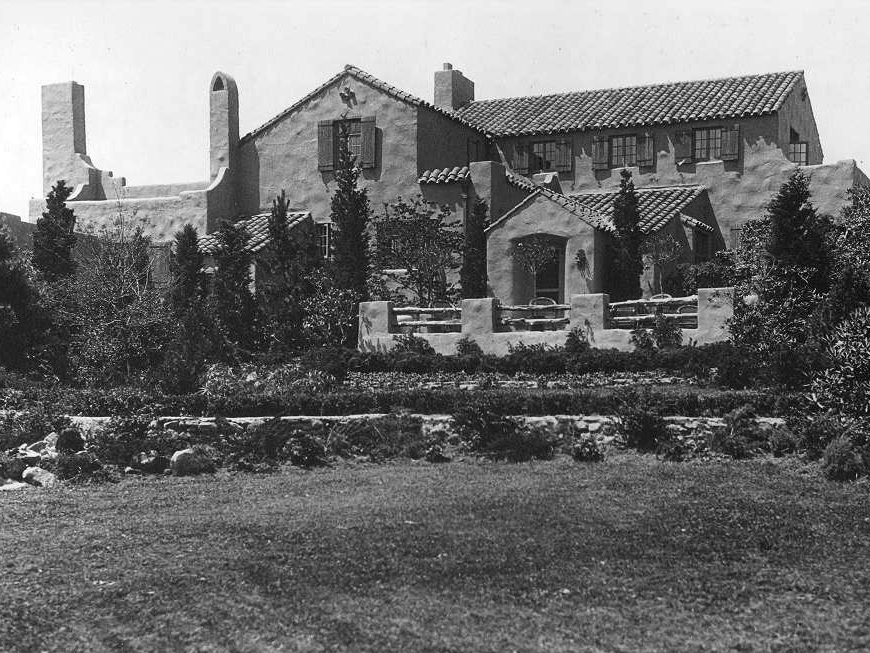

Bordered by today’s Flamingo Road, Tuthill Road, and Fireplace Road, and fronting on Fort Pond Bay, Tuthill’s Pond, overlooking the Old Fishing Village, architect Andrew Thomas (1875-1965) designed the entire thirteen-acre estate, including the Moorish style house in the 1920s. Thomas was famous for designing low-cost apartment complexes with green areas. Much of his work was accomplished in New York City. He was later appointed New York State Architect and built several hospitals.

There were numerous greenhouses on the estate, stocked with tropical plants and experimental fruit trees. He added ponds and a riding track, typical components of a Gold Coast estate so prevalent on Long Island in the early twentieth century.

In 1936, Elbert McGran Jackson (1896-1962), an illustrator for the Saturday EveningPost and other publications, purchased the estate and set up a silk screen fabric factory in the greenhouses and designed upholstery fabrics, draperies, interior screens, and wall coverings for upscale New York City interiors. While at Montauk, Jackson did some paintings as well. Other notables, such as artist Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) worked at the estate.

Longtime Montauk resident, Elizabeth Job (1923-2006) said the estate was a real showplace when Mr. Thomas was there. It was “well staffed with everything cared for to perfection. The manicured lawns were a complete contrast to the surrounding wild grass covered hills of Montauk.” There was even a watchtower!

Job also recalled “a menagerie of animals inhabited the acres – some in cages – some free to roam. Exquisite peacocks with their colorful plumage seem to be the most remembered, although there were unusual animals, such as gazelles.”

By 1960 the buildings showed signs of neglect. Eventually the property was subdivided into fifteen lots in 1988, but most of the estate remained as open space.

Wyandannee Inn

In 1915 Hilda Smith (1887-1958) opened the Wyandank Inn on the Old Montauk Highway about a mile from the Montauk Lighthouse. According to her daughter, Mary Smith Fullerton (1915-2009) in Peg Winski’s book, Montauk: An Anecdotal History, Hilda told her husband, Knowles Smith (1889-1978), “If you want to sit in the Coast Guard Station (at Ditch Plains) and smoke your cigars you can – but I’m going to start a business!” The Inn thrived, becoming well known for Hilda’s “excellent chicken and shore dinners,” until a fire of unknown origin destroyed the Inn on the night of November 11, 1926, leaving nothing “but the foundations, kitchen stove and sink,” Hilda was determined to rebuild, and two years later the Wyandannee Inn opened very near the site of the former establishment.

Given the remote setting of the Inn, it proved an ideal place in aiding storage of illegal liquor during the Prohibition Era of the 1920s.4

The Inn proved to be a place of refuge during the great hurricane of September 21, 1938, although Mary recalled “one of the gazebos on the property was picked up and blown off the cliffs, the other lifted off the ground, whirled, and landed in the middle of the road.”

During World War II, the property was taken over by the Army to create Camp Hero, forcing the Smiths to leave. Mary said the military “installed showers [in the Inn] for the men and buried all the bathtubs in the woods.” This marked the end of the Wyandannee’s days as an inn.

The first signs of the ultimate takeover of the surrounding area by the Army were seen in advertisements in the East Hampton Star in January and February of 1942: “SECOND HAND FURNITURE—Reasonable. Wyandannee Inn, Montauk. Knowles Smith, phone Montauk 2405.”

After the war the once popular Inn stood abandoned for a number of years (graffiti on shower room walls indicated its last use was in 1956). Falling victim to vandalism, the once beautiful three-story structure was burned down as part of a drill by the Montauk Fire Department and a number of neighboring departments in October, 1967. Nothing marks the site today, along what was once the active Montauk Highway (later Old Montauk Highway), and currently the entrance road to Camp Hero State Park.

Hither Plain Life Saving Station/Coast Guard Station

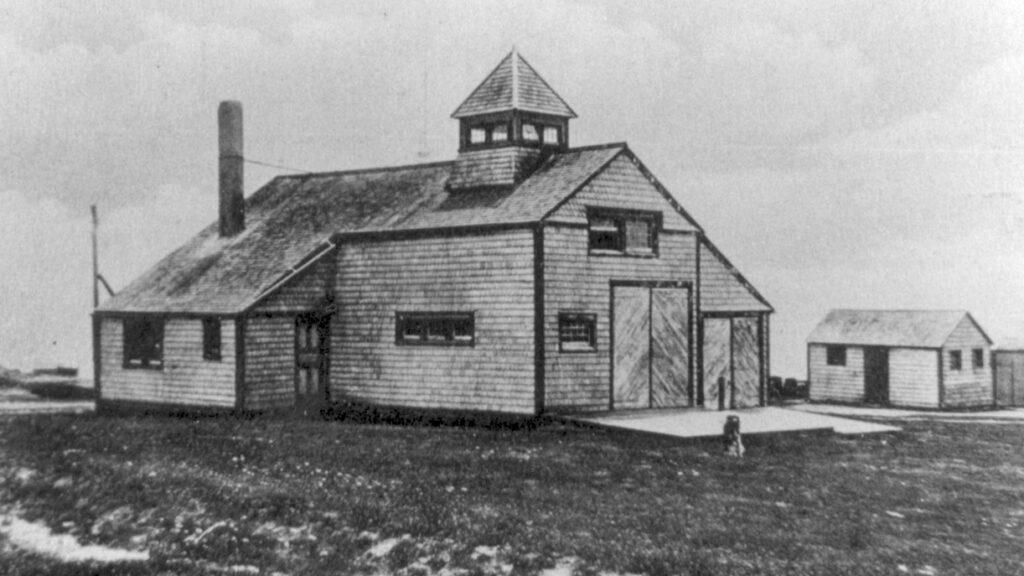

The establishment of the lifesaving service in 1849 resulted in the creation of a number of stations along Long Island’s south shore, three of which were on Montauk, one at Montauk Lighthouse and at Ditch Plains to the east. Land was conveyed in 1855 for a station at Hither Plain, but a building was not erected until 1872.

The first keeper was George H. Osborne (1832-1899), appointed on December 9, 1872. Viewed as a man of “notoriously intemperate habits…drunk on several occasions…and always ready to drink with every Indian who might have a jug of rum,” 5 he was finally removed in 1881.

George E. Filer (1839-1908) took over as keeper. During his time at Hither Plain, the station was enlarged. William D. Parsons (1860-1940) became keeper in 1892 and served for twenty-five years.

When the U.S. Coast Guard was formed in 1915, Hither Plain became Station No. 66. During World War I, a watch tower was added to the site in 1917, soon followed by a new boathouse.

Hiram F. King (1882-1954) became keeper in 1917 and served for three years. Thereafter, the position of keeper was vacant, and the station was discontinued in 1922.

Though generally inactive in the early 1920s and ordered closed, the station was reactivated in 1924 during the Prohibition Era to try to control bootlegging when Montauk became a center for liquor “commerce,” with numerous landing places for loads of rum and other liquors. With the end of Prohibition in 1933, the station was listed as inactive soon later.

The station was revived during World War II, when it was used as a Loran (long range navigation) station. Across the road (Old Montauk Highway) from the station, the Parsons Inn was used as a barracks for servicemen.

The station was abandoned in 1948 and the buildings razed shortly thereafter. The station stood on the south side of Old Montauk Highway across from Washington Avenue. No marker notes the existence of the station, just a grassy clearing overlooking the Atlantic.

1 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “Pedestrian Trip Around Long Island,” July 12, 1859. Visitor not named.

2 East Hampton Star , Oct. 31, 1968, “Memories of First House at Montauk,” recollections of William Bassett who lived there 1903-1906

3 East Hampton star, “Bathing Casino Becomes Surf Club,” July 18, 1930.

4 Montauk: An Anecdotal History: Tastes, Traditions, and Trivia, ©1997 By Peg Winski”

5 In a letter by Henry E. Remington of Jan. 2, 1878