by Ariana Garcia-Cassani

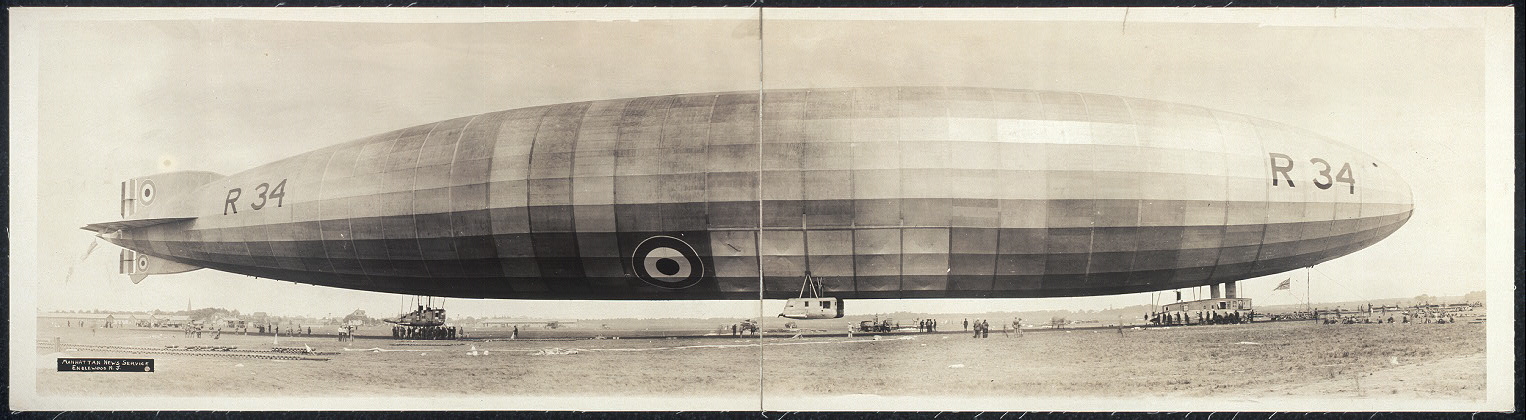

On July 6, 1919, British dirigible HMS R34 passed the Montauk Point Lighthouse on the first east-west air-crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. A few weeks earlier, a pair of aviators, John Alcock and Arthur Brown, made the first non-stop air-crossing of the Atlantic Ocean: beating the R34 to the title. Alcock’s and Brown’s voyage was full of difficulties: broken electrical generators, non-functional radios, a freezing snowstorm, bouts of impenetrable fog, a dangerous nosedive and, lastly, a dangerous landing in a bog mistaken for a grassy field. The flight of R34 similarly depended on the skill and experience of its crew to complete a successful flight.

R34 left East Fortune, Scotland on July 2, 1919 with a thirty-person crew and 4,900 gallons of petrol. The crew included eight officers — some already renowned airmen. Major George Herbert Scott, leader of this expedition, a member of the Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Air Force during World War I, also made significant contributions to airship engineering; notably, he worked on evolving the mooring mast. Brigadier General Edward M. Maitland famously flew 1,117 miles (a record distance) from London to Mataki Deremi, Russia in 1908. He also wrote a published account of the R34’s crossing edited by Rudyard Kipling.

Beyond officers, the crew mostly consisted of riggers and engineers. Riggers supervised the hydrogen-filled gas bags: constantly checking for leaks detected through changes in pitch. Music and song were not only entertainment on this airship, they were tools utilized by the crew: they were encouraged to whistle and sing onboard as to more easily detect unusually high pitched noises. They also utilized a gramophone playing Henry Pether’s Wild, Wild Women or music sung by Miss Lee White, famous British actress and singer. Not only did riggers repair gas bag leaks near the crew’s quarters, they also walked on the scaffolding outside of the ship to check for rips and damage. Oftentimes, experienced riggers decided against using a rope that would anchor them to the ship and catch them if they fell. Instead they trusted their balance and kept their footing by leaning into the wind. Engineers were mostly concerned with the five engines that propelled the ship forward and required near-constant attention. The Royal Air Force had decided to reserve Rolls Royce engines for aeroplanes, so the R34 was outfitted with Sunbeam Maori engines designed by Louis Coatalen, which were less dependable than those made by Rolls Royce.

The crew of R34 even had some unauthorized additions to their ranks. It was the first airship to carry stowaways: one human and the other feline. When human William W. Ballantyne was informed, soon before hop-off, that he would not be making the historic journey, he hid on the R34 between two airbags. He successfully evaded detection until the second day of the journey when he was discovered with a 102 degree fever. After a period of rest, during which he recovered, he went to work helping the crew. When questioned about why he disobeyed orders risking court-marshal, Ballantyne explained, “I’d worked hard, I had, blasted hard, on the bally blimp, but that didn’t matter so much. You see, I’d never been to America, had my heart placed on it, and my mind, too.” Ballantyne was very nearly delighted when told that he would not be flying back to England on the R34, explaining that he was interested in fighting United States lightweight champion of the time, Benny Leonard (also known as Benjamin Leiner). He hoped to do so before he was sent home. The second stowaway was a cat named Whoopsie. Both unauthorized passengers are in the photo above – Ballantyne is the second man from the left and Whoopsie is sitting to the right of the gramophone.

Despite their expertise and planning, the crew encountered unpleasant weather for much of their journey. Flying westward in the northern Atlantic, R34 was moving against prevailing winds. They frequently ran into storms with strong gusts that slowed their progress and chilled the crewmen. The R34 was large and not prone to quick jerky movements, but one of the storms was fierce enough to endanger crew members. While engineer J.D. Shotter was lying along a drogue hatch (a hatch that leads to a drogue, a conical device that is towed behind an airship to slow it down) the R34 was caught in a squall, causing the nose of the dirigible to tip downward. Shotter almost fell out of the open hatch – stopping his descent only by hooking his leg around a girder.

As the trip extended beyond its expected timeline, the crew ran low on provisions. Thanks to limited bathing water, the crew was described as “distinctly dirty” by the time they reached the North American coast. They were also running low on fuel, a major concern for the vessel. They contacted military offices in Boston and Washington D.C. to ensure they would be able to land in an emergency. The R34 was prepared to land in Boston or Montauk if need be and they requested US navy battleships be available if the dirigible needed to be towed to land.

Amazingly, on July 6th, the R34 finally encountered favorable weather and flew by Boston and Montauk without needing to stop. The East Hampton Star reported that, “The airship passed directly over the station [Montauk Naval Station] and the crew could be plainly seen seated in their comfortable quarters.”

The keeper of the Montauk Point Lighthouse recorded seeing the R34 with the following entry: “British dirigible R34 passed this Station at 7 o’clock that AM about 2 miles North of Station on a westerly course from overseas (the first dirigible to cross the Atlantic).”

Major Scott and his crew made it safely to Mineola with only two hours of fuel left (140 gallons) a precarious success to which Maitland said, “…we couldn’t have cut it much finer, and are lucky indeed to get through!” Unfortunately, because of their earlier fears of fuel depletion, the trained landing crew had been sent to Boston to dock the airship in the Massachusetts city. There was no one in Mineola to coordinate a landing. Major J. E. M. Pritchard parachuted down from the airship in full dress and directed U. S. military men in safely landing the dirigible.

Once they disembarked, the British crew were met with uproarious cheers and dozens of cameramen and reporters.

During their three days in the United States, crew members had a varied experience. Some enjoyed a reception at the Garden City Hotel, while another attended to a toothache at a Manhattan dentist’s office, and all were congratulated by President Woodrow Wilson.

The journey back to Scotland was slightly less eventful thanks to favorable prevailing winds. Despite some engine failures, there were fewer headaches. The HMS R34 deserves to be remembered as having made the first successful round trip by air across the Atlantic.